Kia ora from Jess,

For many of us across different communities, living in a society that cares for people and the environment matters deeply. Many of us want to live in ways that nurture our connections with each other and the environment that sustains us.

In our society, right now, we know people are suffering, we know that we’re damaging the environment, and we know that it is so possible to fix. So why are our decision makers not taking sufficient action? It’s unjust. I feel so frustrated.

I feel this way because the things that matter most to me, wisdom, helpfulness, pragmatism, justice, and care for the environment are not being prioritised by people in the institutions who decide how our shared resources are used.

Doing research on the mindsets people hold, the narratives that shift them, and the communication that can spark action is a way for me to address this intense frustration.

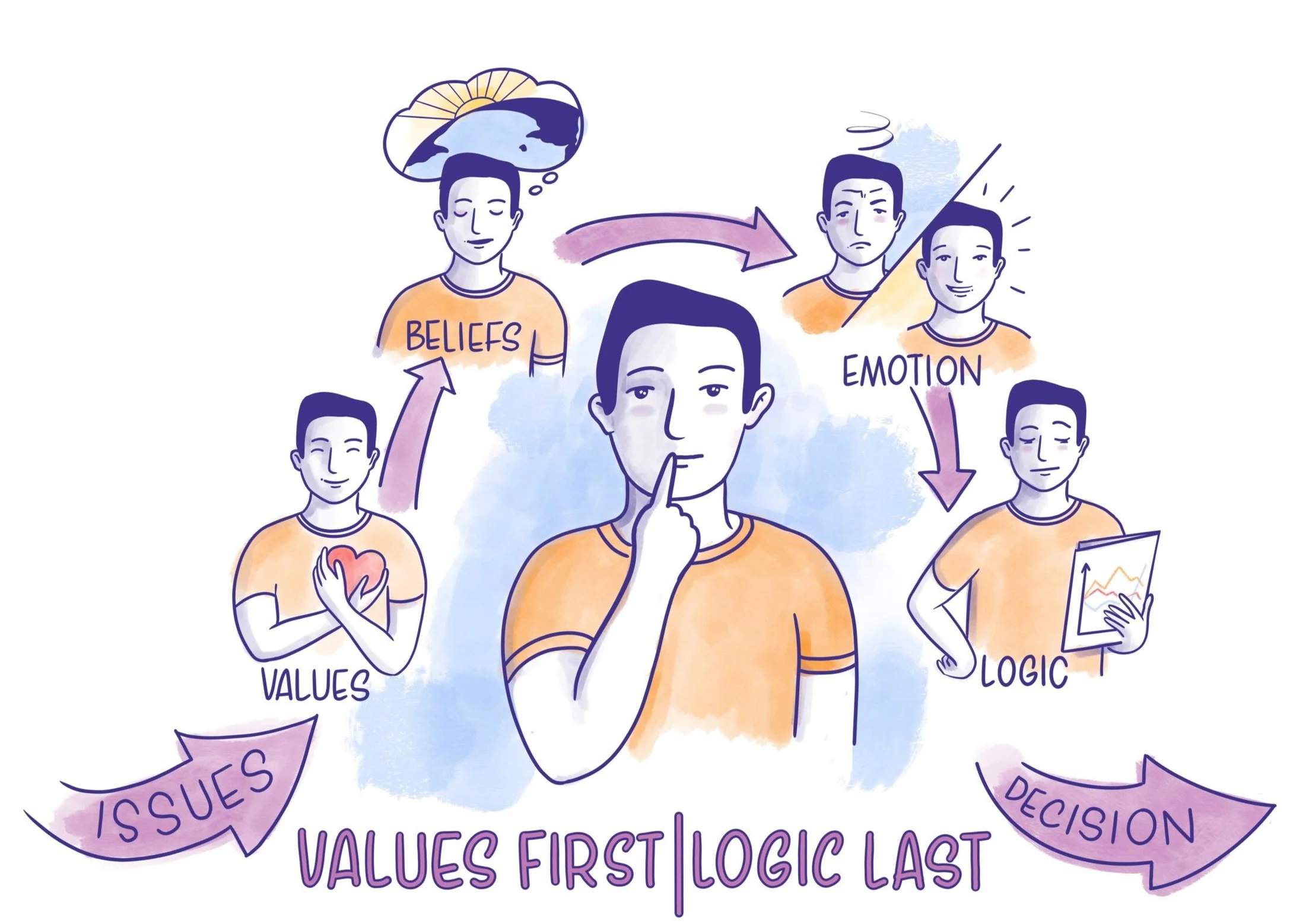

What I have just described is the values - beliefs - emotions - decision - action ‘cognitive chain’. It is a process that explains why values framing is so important if we want to deepen people’s understanding about complex issues and build support for change.

What are values?

Values are our core motivating force, our why of life. We hold many values, and tend to prioritise particular types of values. Our prioritised values can change across time and experience.

Researchers have identified many different values that are common across cultures and societies. One aspect of values research has researchers look for values based on similar motivations in order to organise them into values domains or dimensions. One particular domain or group of values recurs across the research - this is a group of values I will call prosocial. Prosocial type values tend to come with internal, inherent or relational rewards as a motivation. These prosocial values domains can also be called self-transcendent, intrinsic, altruistic, self-direction values.

There is also a group of values researchers have identified that are about self or external material rewards, which are sometimes called extrinsic or self-interest values. The two broad domains I have highlighted here: prosocial and self-interest (there are others) tend to act in conflict with each other, and as such are hard to prioritise at the same time - it is hard to prioritise personal achievements and wealth at the same time as prioritising more intrinsic motivations like love and protection of our natural environment. Though we can prioritise different values at different stages or in different contexts.

How do values affect how we think about complex issues?

Values are important because we filter all the information we received through our values. When we get new information we subconsciously consider ‘does this information fit (or not) with the values I’m bringing to this issue, and what I believe?’ Because this is usually a very fast subconscious process we get a nervous system signal - our feelings. We may feel angry, outraged, soothed, joyful, confronted, perhaps even disinterested or bored when we hear new information.

These feelings will guide our decision making about that information. We may ignore the information, it may influence our intentions, or we may act on it in particular ways. We apply logic at the last stage. We use data and facts to justify the decision we have already made based on our feelings. Which means I may be using the information in an accurate way - or I may not.

Different values affect our decision making differently

Different values affect how we think and the decisions we make differently. When people prioritise prosocial values they are much more likely to consider how the issues affect the collective, support solutions that benefit public good, and act in prosocial ways. Reliable and robust research into our deeply held values shows that most people tend to prioritise prosocial values (not all though!).

Why then are people not acting on these prosocial values all the time?

Social context influences the values we bring to decision making

While research shows most people tend to prioritise prosocial values, we don’t automatically bring those values to all the information we consider. The culture we live in and the narratives we’re surrounded by play a role in which values we bring to decision making.

In western cultures, our narrative environment is mostly controlled by powerful people and groups with particular commercial or political interests. It tends to be dominated (though not solely occupied) by self-interest values. In the UK for instance, when asked people say that most institutions - arts, media, government, education - promote self-interest values. You can read more about that research by the Common Cause Foundation on their website.

In general, self-interest values are the backdrop to decision making about all sorts of things. People can still bring their prosocial values to decision making, but it is strongly influenced by our social context. And unfortunately, if we think other people only prioritise self-interest values we are much less likely to act in prosocial ways ourselves. We might think “well I'm a good person but the rest of you are clearly all only in it for yourself, so what is the point?” However, it works in the opposite direction too, researchers have observed in experiments and in the real world, we see a virtuous cycle of prosocial thinking and acting when we see others thinking and acting in prosocial ways.

Framing also influences the values we filter information through

Just as our social context influences the values we bring to decision making, so does our information context. There is no such thing as neutral framing. When we receive a piece of information we can also receive direct signals in the framing of that information about the values that matter. When people tell us that we should act on climate change now because it will make it much harder to make money from our current way of life, the communicator is telling us we need to bring our self-interest values (like money and wealth) to our thinking about the issue.

This self-interest framing makes it harder for people to assess how climate change information and proposed solutions relate to their prosocial motivations. It makes it even harder to act in prosocial ways. People may instead think that because this change will cost money now (which they’ve been told matters most) it’s not a good idea to progress the policy.

Another way that communicators unintentionally influence the values people bring when considering prosocial issues is when they try to create values-free communication. This usually looks like factually driven presentations of information about the issue. When communicators try to provide values-free information, people can’t see that their prosocial values are relevant at all, and will often draw on values that are dominant in the social context or they believe most others hold.

Remind people of the values they hold that are most relevant to prosocial issues

If we want people to understand collective issues and take prosocial action, we should frame the information through the values they already hold that are most relevant to the issue. Their prosocial values.

The good news is experimental and real life research shows this works on issues, from covid through to the environment, and with a wide range of people who hold a wide range of values. This is called priming people’s values.

For example, if we want to help people understand that local government need to make decisions for the public good over the long term, including for the climate for example, then framing conversations in values that relate to these issues - like pragmatism and care for the places we love - will help people to process the information effectively.

That might sound as simple as “Making wise and sensible decisions about how to allocate our shared resources for the most public good, including how to protect the natural environment we love, matters to many of us. People in local government also have a focus on the long-term, especially in terms of protecting our environment that sustains us, and are looking at allocating resources so that future generations can also thrive.”

Showing people their values are being transgressed sparks emotions - some will be intense

When we remind people of the prosocial values they hold as part of framing complex information, we should not expect to simply create feelings of happiness, joy or a sense of excitement. Emotions span a vast range of physical and mental processes. At the start of this piece, I shared my feelings of frustration and anger, which are common emotions, as is sadness. All these emotions are appropriate when framing prosocial values and explaining how they are being transgressed by current activities or inaction. If there are huge injustices happening and people’s values are being transgressed we would expect them to feel angry, sad and frustrated. Especially when we want to spark people to act as citizens in support of prosocial policies.

However, we should never aim to create that anger or sadness through fear framing. That is opening our communications with fear of “the other”, a bad event, of an apocalyptic world for example. Fear is not a prosocial value. Too often fear-led framing leads to less expansive, less inclusive, and less humane responses as peoples’ fight or flight response kicks in.

In the case of the climate crisis, prosocial values framing might start with reminding people there are many places in their local community they love, places they visit that they love, the beaches, the rivers, the mountains, the bush that they love and want protected. We then need to explain the reliable information that the current approaches are simply not enough to protect these places, even in our lifetime. We remind people that action at the scale and pace required has not happened yet, and this in the context of what they value, is definitely not cool. People should feel angry and frustrated at this point. They may feel sad. We can and should create space for this, but we must not leave them with these feelings and nowhere to go with them. This is where solutions, action and ultimately hope comes in.

We need to give people hope that something can be done

When our communications connect with peoples’ values, when they understand through the data we present that their values are not being prioritised, and when they feel their big feelings, they also need to see that there are solutions. They need to know that there are wise, pragmatic and known things that we can and should do. They need to know how they can contribute to making them happen. Hope is essential for directing big emotions in constructive ways.

We can create hope in our communications by talking through the solutions. We can show the pathways to change, name the people responsible (especially those with more power), and lay out how people can support these solutions. We can talk in terms of their role as community members, people, citizens (as opposed to consumers and individuals) who can join with others to create change. We can let them know this work can be done and is being done.

Structure your stories to help people process and and respond to your information through their values

Whatever story you’re telling, the following formula works with what science tells us about how people process and respond to information through their values.

Open with prosocial values and a concrete description of the world that is possible

Explain what is getting in the way - you can use your reliable data and facts to deepen understanding and show how people's values are not being prioritised

Finish with solutions and action to build a sense of hope and purpose

If you’d like to learn more about values and the role they play in narratives for change visit our training page for Foundations and topic specific courses in Climate and Reframing Crime and Justice

This blog with selected references are available to download in PDF format.